By Rakesh Gupta Nichanametla Ramasubbaiah

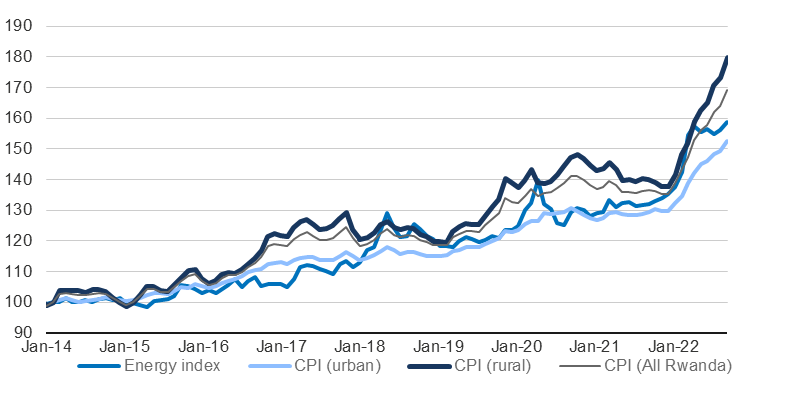

Rwanda has been hit hard by inflation rises, with data indicating it is among the top ten countries worst hit by food price inflation. What started with the global supply chain crisis and accelerated as a result of the Ukraine armed conflict continues to transmit shocks in Rwanda through higher fuel, food and commodity prices, impacting vulnerable communities the most.

World Food Programme (WFP) market monitoring data[1] solidifies this picture of rising food prices. Estimates show inflation of 11.5% between May to June 2022 and a 54% rise compared to June 2021. The National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) furthermore noted a 41% food price increase between September 2021 and September 2022.[2]

For refugees in Rwanda, this is detrimental. Rwanda hosts approximately 127,000 refugees, asylum seekers and others of concern populations. Most refugees originate from the Democratic Republic of Congo (59.93%) and Burundi (39.53%), and 90% live in five refugee camps located across the country.

Figure 1. Monthly headline inflation trends in Rwanda

Chronic vulnerabilities of refugees in Rwanda

Refugee households have always been vulnerable, but the latest inflation appears to have severely affected them. Refugee camps in Rwanda are primarily located in rural areas where, according to data from NISR, communities are being impacted more by inflation – 3.8% more compared to their urban counterparts.

In this context, refugees are increasingly resorting to negative food-based coping strategies such as eating fewer meals a day or limiting portion sizes. UNHCR has also observed an increase in violence against women and petty theft as refugee households become frustrated at their inability to provide for their families.[3]

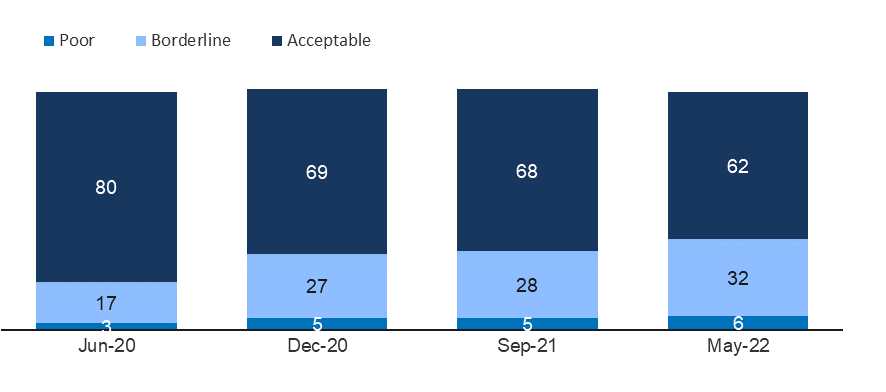

In addition, according to the Joint Post-Distribution Monitoring (JPDM) – an assessment carried out by UNHCR and WFP to monitor the evolving needs of refugees in Rwanda, including the effects of targeted food and non-food assistance – the share of refugee households suffering from poor food consumption has doubled over the last two years: from 3% in June 2020 to 6% in May 2022. At the same time, households facing borderline food consumption have nearly doubled from 17% (June 2020) to 32% (May 2022).[4] All in all, these statistics paint a picture of a deteriorating situation for refugee communities throughout Rwanda.

Figure 2. Prevalence of food consumption (% of refugee households)

The chronic vulnerabilities faced by refugees are compounded by their limited economic activities and employment. Almost half of refugee households (48%) report that they are not involved in any productive activities. Among households who are generating income, they report spending most of their income on food. On average, refugees are spending 76% of their household budget on food – a significantly higher proportion than had been reported in previous years.[5]

What does this mean for food assistance delivery?

Refugees in Rwanda currently receive monthly food assistance mostly in the form of cash. Since May 2021, this assistance has been delivered on a targeted basis in recognition of the fact that not all refugees are equally vulnerable. A targeted approach also ensures limited resources are utilized in the most effective way.

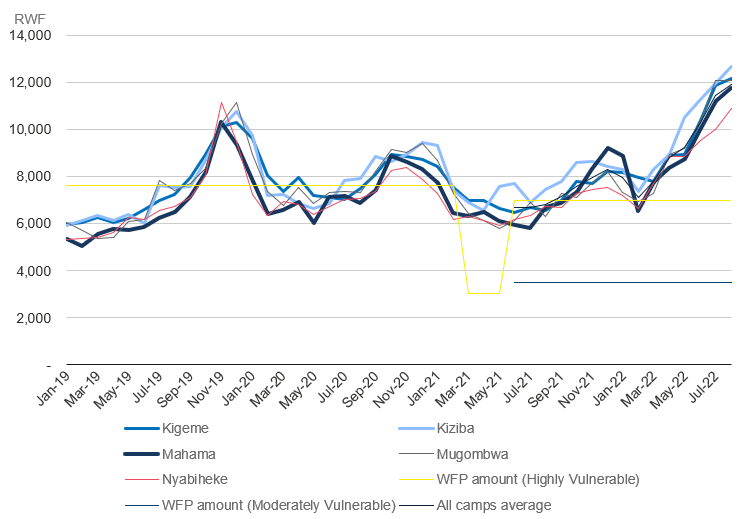

Based on this, refugee households are currently split into three groups, taking into consideration their protection needs. Some 86% of refugees are classified as highly vulnerable and are supposed to receive RWF 7,000 (USD 7) of food assistance per person every month, while 7% are classified as moderately vulnerable and supposed to receive RWF 3,500 (USD 3.50). The remaining are classified as least vulnerable and do not receive cash-based food assistance. However, funding support for the refugee operations in Rwanda is insufficient to even fully meet the current requirements without taking into account inflation. WFP thus has been forced to implement ration cuts since May 2021.

Despite having a targeting approach that directs higher levels of support to more vulnerable families, high inflation has cut back the amount of food families can afford. Data from WFP that tracks the minimum food expenditure basket suggests that the recent rise in prices has translated to a severe shortfall in the current level of food assistance.

UNHCR estimates show that as of August 2022, food assistance would need to increase by 74% (RWF 5,161) in Kigeme refugee camp; 81% (RWF 5,656) in Kiziba; 68% (RWF 4,762) in Mahama; 72% (RWF 5,073) in Mugombwa; and 56% (RWF 3,892) in Nyabiheke to keep assistance rates on par with current market prices.

Figure 3: Food inflation, price data from the markets around the refugee camps, monthly

Shock responsive assistance in the medium to long term, and increased support in the immediate term

To conclude, there are two solutions we propose: first, in the longer term, it is worthwhile considering a shock-responsive, flexible assistance distribution system that matches the amount of cash assistance to the current market prices of the food minimum expenditure basket. While inflation is now leading to an increased budgetary need to help refugee communities meet their minimum nutritional needs, by the same token, lower prices could result in budgetary savings.

When comparing the amount needed to purchase the food basket across the five refugee camps and the assistance delivered between January 2019 to August 2022, prices for the food basket were on average lower than the assistance amount in 16 different months. A shock-responsive assistance distribution system that allows for adjustments of assistance could be more effective in helping refugee communities cope with changes in the wider economy.

Second, in the immediate term, the global community, as highlighted at the recently concluded High Level Event ahead of UNGA77, needs to increase its support to refugees in Rwanda and elsewhere as UNHCR faces a funding gap of more than $700 million to the end of the year.

[1] The WFP market monitoring system was set up in November 2016 to collect market information inside and around camps (Nyabiheke, Kigeme, Mugombwa and Kiziba), where most of the beneficiaries’ purchase food from WFP’s provided cash assistance. The WFP cash assistance is based on food basket that comprises of 12.3 kg of maize grain, 3.6 kg of beans, 0.90 kg of oil and 0.15 kg of iodized salt per person per month. Market information is collected once a week, on about 23 commodities (cereals, tubers and roots, oil and salt, pulses, meat, and vegetables) from markets inside and around camps.

[2] NISR, Consumer Price Index (September-2022), Annex 3, p. 8 (published 10 October 2022).

[3] UNHCR-WFP Joint Post-Distribution Monitoring (JPDM) and Participatory Assessments, UNHCR and WFP Rwanda.

[4] The Food Consumption Score (FCS) is used to compute the food security status at the household level. The FCS is calculated from the types of foods and the frequency with which they are consumed during a seven-day recall period. Based on their score, households are classified into three consumption categories: poor FCS (≤21), borderline FCS (21<FCS≤35) and acceptable FCS (>35). Those with poor and borderline food consumption are grouped and classified as having inadequate food consumption.

[5] UNHCR-WFP Joint Post-Distribution Monitoring (JPDM) and Participatory Assessments, UNHCR and WFP Rwanda