Afghan students mark 15th year of German scholarship

Afghan students mark 15th year of German scholarship

PESHAWAR, Pakistan, September 18 (UNHCR) - Albert Einstein was a refugee from Nazi Germany, but half-a-century after the great scientist's death his homeland is helping other refugees around the world to realise their dreams for tertiary education - including scores of Afghans.

This year marks the 15th year of the Albert Einstein German Academic Refugee Initiative (DAFI) in Pakistan - one of the largest and longest-running German-funded scholarships in the world. The programme aims to contribute to the self-reliance of refugees by providing them with professional qualifications for future employment.

"DAFI is a real investment in the human resources development of all the countries whose young people are displaced and are unable to continue tertiary-level education," said Nasir Sahibzada, UNHCR's programme assistant for education in Peshawar, capital of the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP).

More than 900 Afghan refugees in Pakistan have benefited from the programme since it started in 1992. A total of 72 students are now studying in 26 academic institutions in NWFP, Balochistan, Punjab and Sindh provinces.

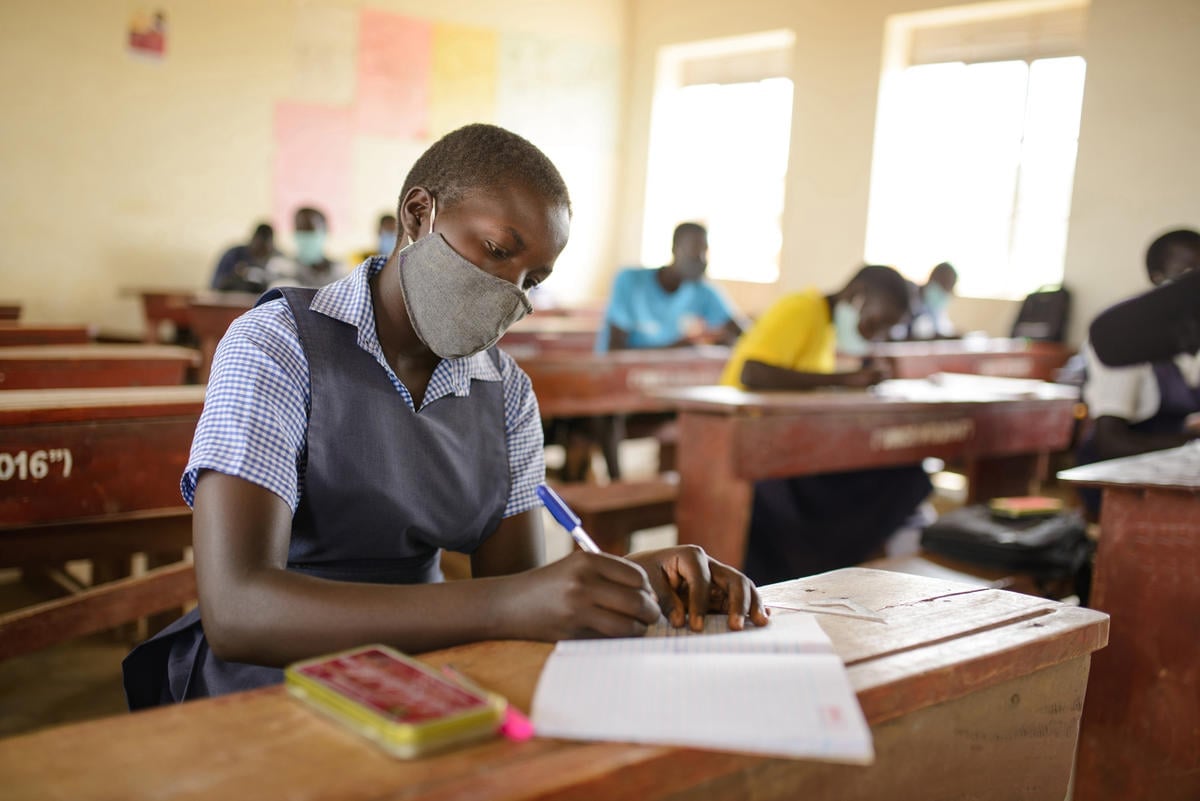

Earlier this month, some of these students took part in a one-day workshop in Peshawar for DAFI scholarship recipients. They discussed education-related problems and recommendations.

"It is only because of UNHCR and DAFI that I am able to fulfil my dreams," said Afghan refugee Saleema Azimi. "I am studying biotechnology, a relatively new field. I am sure I can accomplish a lot."

Fellow student Tayaba Naqibullah displayed equal confidence and ambition: "I am doing my Masters in Public Administration. Once I complete my education, I will go back to Afghanistan and work for the rehabilitation of my country, especially for Afghan women. I want to tell the entire world that although the major part of our lives was spent under domination, now the situation is different and we all have the desire and ability to change our country."

UNHCR's education officer, Claas Morlang, was at the workshop to answer queries. "It was very impressive to see the young generation of Afghanistan, especially women, manage and succeed at the university level," he noted. "Their enthusiasm is remarkable. They are determined and have the strength to learn and contribute to the community."

Even with the will and financial support to succeed academically, Afghans still face obstacles in their quest for higher education, including the complicated admission procedures to Pakistani institutions.

Currently, Afghan students who wish to enter Pakistani institutions must take an exam with the education cell of the Commissionerate for Afghan Refugees. Those who pass are recommended to the relevant department, where they will pay the same fees as local students. Afghan students who approach the institutions directly are considered foreigners and have to pay three times the amount.

Another challenge is the gap between different levels of education available. Consistent with its worldwide policy, UNHCR provides basic education to some 100,000 Afghan children in more than 270 camp-based primary schools in NWFP, Balochistan and Punjab. The Pakistan authorities had provided middle and secondary school education until funding problems forced them to close the schools in March this year. Efforts to find alternative sources of funding have so far been unsuccessful.

According to a 2005 government census of Afghans living in Pakistan, an estimated 55 percent of the 3.04 million Afghans counted were under the age of 18. More education initiatives like DAFI are needed to enable young refugees to contribute to society in exile and upon repatriation.

By Rabia Ali in Peshawar, Pakistan