The plight of South Sudanese refugee children--reflections of the Regional Refugee Coordinator

The plight of South Sudanese refugee children--reflections of the Regional Refugee Coordinator

“The leaders should do something about it. They should see the people’s suffering, the hunger and displacement, and show consideration. Right now, I see no future.”

Wise words from 16 year old John, a student at Sud Academy, a community school in Kawangware on the outskirts of Nairobi, serving children from underprivileged families. He is talking to Arnauld Akodjenou, UNHCR’s Special Advisor and Regional Refugee Coordinator for the South Sudan situation. His precocious outlook belies his young age.

The Regional Refugee Coordinator listens intently. John, a refugee, came to Kenya from South Sudan at the young age of six, with his mother and three sisters. He completed his primary education in a private school, then dropped out for four months—despite having qualified to go to secondary school—because his mother could not afford the fees.

John seems unaffected by rudimentary facilities that make up his learning environment. “I want to be a businessman when I grow up,” he says. “I am good at making deals.” He hopes to study business in university one day, and then return to South Sudan to help build the country.

Sud Academy is tucked at the bottom of a hilly slope, straddling a swamp that collects smelly effluent from residential buildings higher up.

Akodjenou is visibly impressed by the young lad. Still, he is unable to conceal his distress at the conditions of learning. Sud Academy is a far cry from the educational institution that the name evokes. Tucked at the bottom of a hilly slope, it straddles a swamp that collects smelly effluent from residential buildings higher up.

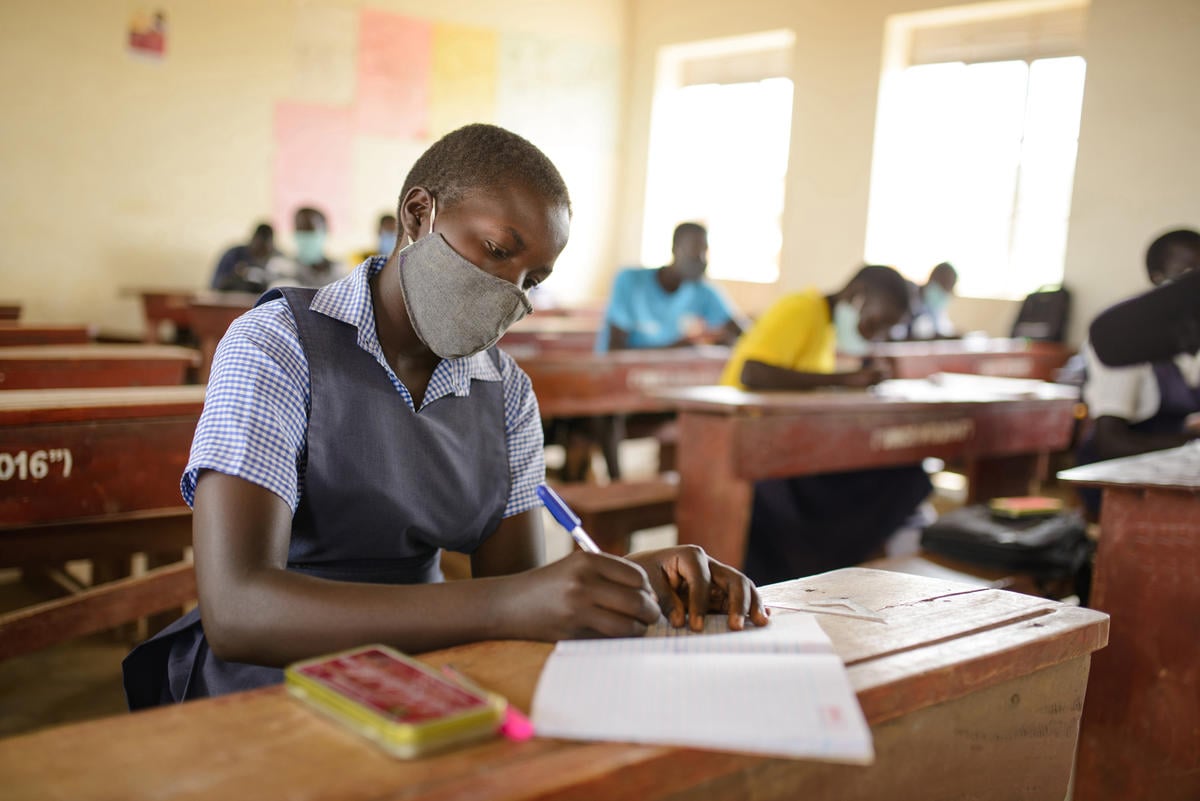

Classrooms are made from corrugated iron sheets with spaces in the walls, so that teachers’ voices carry as they attempt to drown out the noise of traffic outside. Occasionally sounds of matatus (Nairobi's loud, vibrant minibuses) blaring loud music or the screech of braking cars rend the air. During the rainy season, learning conditions are undoubtedly much worse.

Yet, despite these challenges, when compared to the situation of children living in South Sudan, students like John are among the lucky ones who have access to education.

"Let’s hope that those in South Sudan will understand that it’s time to put aside arms and violence—not just for themselves—but for the young people like you who will build the country’s future.”

The students of Sud Academy seem oblivious to these distractions as they share their concerns and aspirations with Akodjenou. None mentions the need for better classrooms, the putrid smell of sewer water, or the incessant noise. Undaunted by their surroundings, these children want to be doctors, lawyers, pastors, pilots and air hostesses. They ask for only text books, a library and a laboratory.

“Your message is loud and clear,” the Regional Refugee Coordinator tells them. “It’s not where you come from, but the education you receive that matters. Let’s hope that those in South Sudan will understand that it’s time to put aside arms and violence—not just for themselves—but for young people like you who will build the country’s future.”

The school bell rings. It is lunch time. John accompanies Akodjenou to the narrow courtyard. Children from the lower classes gather outside the makeshift kitchen, each carrying a plate. Some stop at the water tank to rinse theirs. “Some of the students you see depend on the lunch we get here” says John. “Our school provides the only meal they get to eat in a day.”

“I am worried that too many children of South Sudan are missing the vital markers that will make them healthy and able individuals in later life.”

George Deng, the the principal of Sud Academy underscores the plight of the students. Many live with friends or relatives, and experience great difficulties. Others are heads of households, grappling with adult responsibilities without the necessary financial means. The school has nine classes, and only eight teachers who must cover all subjects in the curriculum. There is a high staff turnover with teachers constantly seeking better pastures, as the school pays only incentives. The school depends on the goodwill of sponsors and cannot offer salaries. Still, Sud Academy is steadfast in its mission is to help less privileged children, including Kenyan citizens, to lead better lives.

Akodjenou reflects with disquiet the situation of South Sudanese children. “I am worried that too many are missing the vital markers that will make them healthy and able individuals in later life,” he says. “The lost generation created by the South Sudan situation is of great concern. When we deprive these children of proper education, we are destroying their individual hopes and dreams, and doing irreparable damage to the future prospect of lasting peace and development in the world’s youngest country.”

"The lost generation created by the South Sudan situation is of great concern."

Sud Academy as a microcosm of the South Sudan refugee situation. Key challenges in education across the six countries hosting South Sudanese refugees include insufficient infrastructure with many children learning in dilapidated tents and temporary structures. There are the overcrowded classrooms accommodating 100 children, and pupil-teacher ratios of approximately 80:1. Limited secondary school access leads to very low enrolment. For refugees in French speaking countries (Central African Republic and Democratic Republic of Congo) the language barrier is a major problem.

54% of the 983,842 South Sudanese children of school going age are out of school.

By 1 September 2017, there were 983,842 children of school going age representing 49% of the 2,007,841 strong population of South Sudanese refugees. 54% of those children are out of school. Disruption to learning must be minimized and children engaged constructively to deal with the impact of conflict and displacement. Denying them access to education can perpetuate the root causes of the instability in the region.

"Depriving children of proper education is destroying their hopes and dreams, and doing irreparable damage to the future prospect of lasting peace and development in the world's youngest country.”

In September 2017, UNHCR issued its second annual education report entitled "Left Behind: Refugee Education in Crisis".

More than 3.5 million refugee children aged 5 to 17 did not have the chance to attend school in the last academic year, UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, says in a report released today.

These include some 1.5 million refugee children missing out on primary school, the report found, while 2 million refugee adolescents are not in secondary school.

“Of the 17.2 million refugees under UNHCR’s mandate, half are children,” said Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees. “The education of these young people is crucial to the peaceful and sustainable development of the countries that have welcomed them, and to their homes when they are able to return. Yet compared to other children and adolescents around the world, the gap in opportunity for refugees is growing ever wider.”