The need for differentiation and the role of mass customization.

No community is homogenous – meaning there is no ‘silver bullet’ or one ‘best channel’ to communicate via. Everybody accesses and consumes information in a different way – we are all unique. Therefore, multiple communication channels are critical – the fewer channels we use in our community communications the more groups or individuals we are in danger of excluding. It is also human nature to want to be listened to and treated as an individual. An example is how we actively seek out companies that provide individualized service and bemoan automated answering messages or boilerplate responses from customer relation departments.

How do we embrace heterogeneity?

The challenge of the ‘individual client’ has been acknowledged and addressed – to some extent – by the private sector for a number of decades. In 1997, the Harvard Business Review described how focusing on the customer was both an imperative and a potential curse. HBR described how company executives recognized the need to provide outstanding service to customers, but as their needs grow increasingly diverse, such an approach became a surefire way to add unnecessary cost and complexity to operations. Escalating costs and increased complexities are definitely not what UNHCR Innovation wants to bring to operations.

The contexts where we work are already complex enough, and humanitarian financing woefully below the stated needs. Global Displacement has hit a record high, data shows that on average 24 people were forced to flee every minute in 2015. One out of every 113 people on Earth is either a refugee, an internally displaced, or is seeking for asylum. This number is staggering! UNHCR is committed to communicating with the forcibly displaced, and communities who host them. It’s an essential element of our work. But, is it really possible to meaningfully communicate at this scale – especially with those in hard-to-reach locations or dispersed across large cities? How can we ensure we establish channels to listen, assure people we’ve heard them and provide individualized answers and/or services?

Mass Customization: a potential solution?

Is there a way to combine personalization and flexibility in our interactions and our services, at scale and with limited or no increased cost? To help develop potential solutions, I’ve looked to the corporate sector for inspiration. After exploring this a little further I began to wonder if the concept of ‘mass customization’ could provide valuable learning. The term was popularized by Joseph Pine in his 1992 book by the same title, where he describes mass customization as “developing, producing, marketing, and delivering affordable goods and services with enough variety and customization that nearly everyone finds exactly what they want”. The term is often used synonymously with made-to-order or built-to-order products. Classic examples include choosing the RAM specification, screen size, and color of a new Mac, or Levi Strauss & Co.’s customizable jeans allowing for pocket, color and trim modifications.

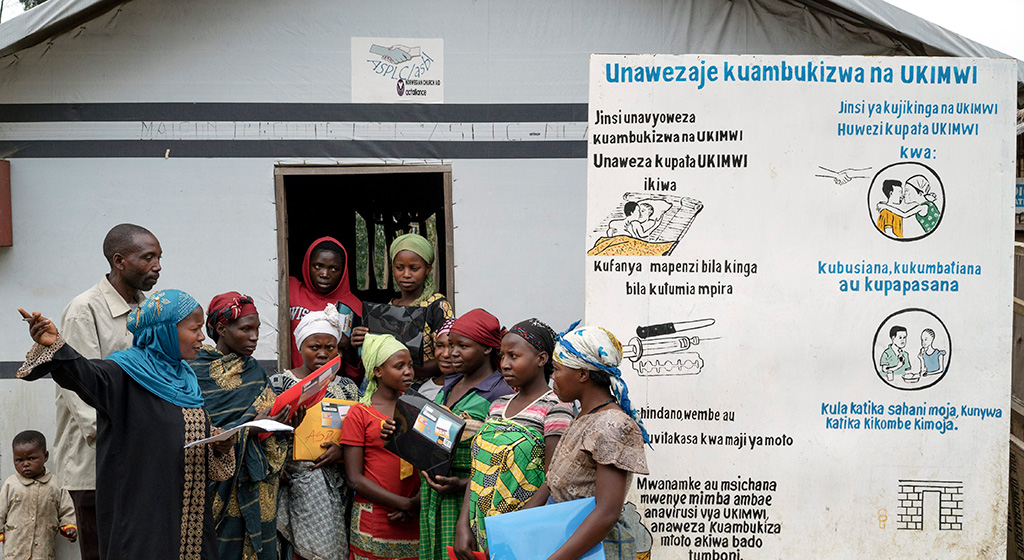

We need to determine what channels of communication displaced populations are currently using, what sources they trust, and how they would like to talk to humanitarian agencies. ©UNHCR/Federico Scoppa

While this sounds great, in theory, I could find few examples of what mass-customization looks like for more abstract ‘services’ – including communication and feedback management. There are also high profile ‘failures’ including the Levi’s ‘Original Spin’ (previously know as ‘Personal Pair’); while there is no definitive rationale for this failure, assumptions include the lack of appropriate or cost effective technology, competition, and a poor return-customer business model. Having read this background, I was a little dissuaded – like many executives – thinking that mass customization is desirable but impractical.

Working towards the ideal

However, research conducted in 2009, by Fabrizio Salvador, Pablo Martin de Holan and Frank Piller, found that mass customization is applicable to most ‘businesses’ but only when viewed as a ‘process’ of aligning with its customers’ needs. They describe how, mass customization is not about achieving some idealized state – in which we know exactly what each customer wants – but it is more about moving toward this goal. In this sense, mass customization is a process – for UNHCR this means working along a continuum towards the ideal: individualized communication and tailored service. What practical steps can we take – as an organization – to embrace the heterogeneity of the communities we work with?

In the research above, the authors identify three capabilities needed to ensure that organizations are able to move along this continuum. Can these be viewed through a Communicating with Communities lens (CwC), to draw out recommendations for the Emergency Lab, UNHCR, and the wider #commisaid community?

Solution Space Development

A ‘company’ seeking to adopt mass customization needs to understand the idiosyncratic needs of customers – rather than identifying common tendencies, it is important to identify where and how the needs most significantly diverge. Once this is understood, it is essential to draw-up ‘parameters’ – to identify the solution space – by clearly defining what can be offered and what can’t. Documented failures of mass customization detail that by skipping this stage, companies fail to recognise customization needs and face escalating costs.

UNHCR translator providing face-to-face information at the Vinojug Reception Centre just inside the Macedonian border from Greece. ©UNHCR/Mark Henley

Within the CwC sphere, this step clearly starts with the information and communication needs assessment process: responders should consult with communities to determine what channels of communication they are currently using, what sources they trust and how they would like to talk to humanitarian agencies. This will include an assessment of the local communication and media landscape, and how information flows through the population. If divergent needs are to be identified it is critical to understand the power dynamics of leadership structures, and the differing needs of the various age, gender, and ability groups. Once these have been identified, responders – at agency or interagency level – need to clearly identify which needs and channels they are able to address and which they cannot. Considerations for which channel to choose must include costing, sustainability, and human resourcing.

Robust process design

Much of the literature for this area focuses on automation and product supply chains – with limited relevance for CwC. However, an important feature of this organizational capability is the concept of ‘modularization’ – combining separate components interchangeably, with standardized interfaces. Again, a lot of commercial ‘industry speak’, but with a definite application within a humanitarian response. The importance of coherent, consistent and timely information sharing in emergencies has been well documented. There are critical components to generating this information that includes the establishment of working groups or other coordination structures, producing key messages, the creation of FAQs and the generation of information sheets. There should also be standard processes, agreed roles and responsibilities, and mapped referrals to establish how information flows between responders and the communities. This can be considered as the ‘standardized interface’.

The modularization concept can be applied to the channels of communication, which can be used interchangeably by a community to access and share information. An individual can, therefore, choose which of the available channels s/he would prefer to use in order to tailor their communication experience. As these multiple channels – for example, community meetings, SMS interactions, hotlines – are components of the whole, they can be mixed and matched by the individual based on their changing preferences and/or situation. The important step that responders need to take is to ensure that these different channels are consistently established as components of the whole information and communications ecosystem; this will ensure the integrity of information being shared and a consistent experience for the individual.

Choice Navigation

The third operational capability is that customers must be supported to identify their own solution, while minimizing the complexity of choice. The commercial world identifies this as the ‘paradox of choice’; having too many choices reduces customer value, leading them to postpone or suspend transactions or classify the seller as difficult to deal with. A matching process, by which an individual’s identified needs are paired with available solutions, helps direct them to the available ‘product’.

This third capability – or lack of – has been identified by CwC practitioners. Examples include communities’ confusion at the proliferation of individual agency or service hotlines, conflicting ‘information portals’ and the pile-up of feedback boxes at health centres or schools. Feedback from communities also often highlights frustration at the number of duplicative discussions and meetings humanitarians engage them in, often scheduled at conflicting times. Recently, there have been efforts to try and reduce the complexity of choice through improved CwC coordination mechanisms. Examples include CwC working groups in Yemen, South Sudan and Myanmar as well as ‘common service projects’ in Nepal and Philippines to name a few. An interagency hotline – for example the one established in Iraq – can direct callers to service providers based on pre-agreed referrals and a decision tree.

Humanitarian responders should ensure that different groups – with their divergent needs – are paired with the multiple solutions. ©UNHCR/Brian Sokol

The ‘matching’ process is critical – communities need to be aware of how they can engage and share information using their preferred channels. Responders should ensure that different groups – with their divergent needs – are paired with the multiple solutions. The advertising of voice-call, SMS, and USSD options for a hotline, or awareness of ‘information points’ within a camp setting are just two examples of this matching exercise. Specific targeted outreach to different groups will help better tailor this pairing – for example alerting women in a community to specific radio shows that are broadcast at times when they indicated they would most likely be free.

Future proofing

It is, therefore, possible to see how the recommendations to strengthen the scope, accessibility, and diversity of our community engagement mirrors learning from the corporate sector. There is a certain ‘validation’ to these recommendations that can be drawn from this process – based on broader experience and body of evidence. As CwC practitioners, we know we need to better understand our communities’ divergent needs and preferences, allow individuals to tailor their interaction with us, minimize confusion and reduce duplication of effort – as does the corporate sector. Equally, as companies increasingly evolve to customized, digitized, have-it-your-way economies, so must we.

In his book, Pine comments that: ‘Anything you can digitize you can customize’. With advances in technology, diverse channels of communication are becoming increasingly accessible – creating better possibilities for customization. Fortune magazine wrote in 1998: ‘If a company can’t customize, it’s got a problem’. If, as humanitarians, we can’t embrace the opportunities of the 21st century then so have we. A hyper-plural communications environment – including digital platforms and multi-function channels – is daunting territory to navigate. However, these are not unchartered waters! By strengthening the organizational capabilities detailed above, we will be better positioned to reach our goal: personalization.

Photo credit: © UNHCR/Kate Holt

We’re always looking for great stories, ideas, and opinions on innovations that are led by or create impact for refugees. If you have one to share with us send us an email at [email protected]

If you’d like to repost this article on your website, please see our reposting policy.